Binding: Kinetics & Thermodynamics

Primary tabs

Binding is one of the essential processes in the cell. It is at the heart of signaling, because proteins 'communicate' via binding events. Molecular machines typically use binding events to trigger conformational changes (e.g., antiporter and ATP synthase). It is key to signaling and to the function of molecular machines. Because most biochemistry is catalyzed by enzymes, binding of substrate to enzyme precedes most chemical reactions. Further, the mass-action formulation, of binding is directly applicable to the analysis of chemical reactions and facilitates understanding energy storage in activated carriers such as ATP.

We will use the symbol "R" for receptor, "L" for ligand, and "RL" for the bound complex. Although it is often the case that R is a protein and L a small molecule, the analysis we develop could apply equally well if L were a second protein.

We will use the standard $\conc{\ldots}$ notation for concentration. Note that, by convention, the concentration of a species refers only to the specific form named. Thus, for the receptor R, which can be either "free" (unbound) or bound, we have

(1)

(1)with a similar expression for ligand L.

Binding Kinetics

In a kinetic picture, we study the time evolution of a binding system using differential equations. We will use the simple (but standard) mass-action assumptions that (i) binding is proportional to the product of R and L concerntrations, and (ii) unbinding occurs in proportion RL concentration.

This leads to the basic equation

(2)

(2)where $\kon$ is the number of binding events per second per unit volume which would occur (nominally) if both $\conc{R} = \conc{L} = 1M$, and $\koff$ is the probability to unbind per second. Note that $\kon$ has to have "funny units", which reference a standard concentration, because a binding event depends on the concentrations of two molecules.

The figure sketches sample solutions of the behavior described by (2). The time evolution of the fraction of bound receptors is shown for two different initial conditions - but a given system will always relax to the same equilibrium. Note that noisy lines are purposely shown: even though solutions to (2) are perfectly smooth, actual behavior is stochastic as sketched.

Binding Equilibrium

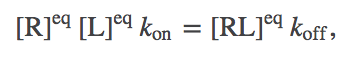

From the definition of equilibrium, we expect the number of binding events per second will exactly balance the number of unbinding events. In a mass-action picture, this condition amounts to

(3)

(3)(In this case setting $d \conc{RL} / dT = 0$ leads to equilibrium only because there are no inputs to, or outputs from, our binding system. In general, setting a time-derivative to zero leads only to a steady state - which could be in or out of equilibrium.)

The equilibrium (3) is usually re-written so that all concentrations are collected together, yielding

(4)

(4)where we have defined the dissociation constant $\kd$ in the last equality. Note that a smaller $\kd$ implies stronger binding.

The equilibrium point - the equilibrium concentrations $\conceq{RL}$, $\conceq{R}$, and $\conceq{L}$ - depends on $\conctot{R}$ and $\conctot{L}$. That is, even for a given type of receptor and ligand, the fraction of bound complexes will depend on total concentrations of R and L. One consequence is that a weaker-binding ligand (higher $\kd$) could result in more bound complexes than a stronger-binding ligand (lower $\kd$) - if enough of the weaker binder is placed in solution.

For reference, we note that the dissociation constant is the basis for defining the "standard" free energy change of binding:

(5)

(5)$\dgbind$ refers to a standard state in which concentrations are measured in molar units. Note that a different choice of units (and pre-factor on the right) would lead to a different $\dgbind$ value for the same system.

Binding Thermodynamics

The thermodynamic equivalent of mass-action kinetics for binding is a mixture of ideal gases. In mass-action kinetics, after all, particles interact only depending on their concentrations: specific interactions - e.g., electrostatic - are not accounted for.

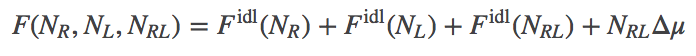

In our model, we will have ideal gases of R, L, and RL particles. We will assume, however, that there is a (free) energy change of $\dmu$ for every bound complex, or $\nrl \dmu$ total. Presumably $\dmu < 0$ for favorable binding, although our formalism does not require that. The total free energy thus consists of the three ideal gas free energies, plus the binding term.

(6)

(6)Note that all three "gases" are in the same volume at the same temperature. The explicit form for $\fidl$ has been derived separately.

In analogy to Eqs. (1), the numbers of particles are not independent because a binding event changes the identity of a molecule.

(7)

(7)The free energy then gives us the probability to observe a given $\nrl$ value via

(8)

(8)The reason for this is explained in our discussion of free energy in a concentration gradient. In brief, the Boltzmann factor of a free energy is defined to be the sum of all probability consistent with the specified condition - the $\nrl$ value in our case.

In the limit of many molecules, the equilibrium point of the system is well approximated by the most probable value, which we can find by minimizing $F$ in Eq. (6). Some algebra is required to get the derivative, but setting it to zero, collecting logs, and exponentiating, yields

(9)

(9)This is the same form as Eq. (4) or (5): the particular ratio of concentrations on the left is seen to depend only on constant parameters of the system. We can see further that the ratio is proportional to the Boltzmann factor of the free energy change per complex formed. In other words, $\dmu = \dgbind + \mbox{const}$.

References

- D.M. Zuckerman, Statistical Physics of Biomolecules: An Introduction (CRC Press, 2010).

- J. Kuriyan, B. Konforti, and D. Wemmer, The Molecules of Life: Physical and Chemical Principles (Garland Science, 2013).

- R. Phillips et al., Physical Biology of the Cell, (Garland Science, 2009).

- K. Dill and S. Bromberg, Molecular Driving Forces (Garland Science, 2010).

Exercises

- Using Eqs. (1) and (2), derive the time-dependence of $\conc{RL}$ in terms of the initial concentration(s) and the rate constants. Hint: The solution is exponential.

- Using Eq. (4), show that $\kd$ is equal to the equilibrium ligand concentration at which precisely half the receptors are bound. This fact enables $\kd$ to be measured by titrating ligand in any experiment in which the measured signal is proportional to concentration.

- Derive Eq. (9).